Why Do High-Intensity Nervous System Practices Stop Working Over Time?

She’s two minutes into the cold shower when she notices she’s thinking about groceries.

Not because her mind wandered. Because the cold no longer commands her attention. Six months ago, this same water felt like an emergency. Her breath would seize. Her body would snap awake. Now it’s just… Tuesday.

That moment is usually how it shows up. Not with failure, but with flatness.

There’s a honeymoon phase to nervous system work, and while you’re in it, you rarely need help recognizing it. In the beginning, things feel different in a way that doesn’t require interpretation. A practice creates contrast. The mind quiets. The body organizes itself. Relief shows up clearly enough that you don’t have to ask whether anything actually changed. It did. You can feel it.

That early phase matters more than we tend to admit. It builds trust. It gives you a lived reference point for what “better” can feel like, which is no small thing if you’ve spent a long time braced, flooded, or shut down.

And then, quietly, the honeymoon ends.

The same practice no longer lands the way it once did. The effect shortens. The signal blurs. You still show up. You still believe in the work. It’s just flatter now. Not broken. Not useless. Simply no longer decisive.

Most people don’t dramatize this moment. They mention it casually, the way you might talk about a song you used to love but now mostly tolerate.

“It worked at first.”

“I still do it.”

“It just doesn’t hit the same.”

This isn’t a problem of effort.

The people who hit this wall are usually the ones who have been showing up consistently, often for years. Nervous system work wasn’t a trend they sampled for novelty’s sake; it was a response to something real. And for a while, it did exactly what it promised.

What makes the shift unsettling is that nothing obvious has gone wrong. The routines are intact. The discipline is still there. From the outside, it can look like stability. From the inside, it feels more like walking the same block over and over again, waiting for something new to appear.

So the conclusion most people reach is dosage.

More time. More intensity. A stronger version of the thing that’s already not working. We are, if nothing else, consistent.

That logic isn’t naïve. It’s inevitable. We’ve been taught that change comes from effort applied steadily and, when necessary, forcefully. High-intensity practices reinforce this belief because they produce unmistakable sensations. You don’t have to wonder whether something is happening. You can feel it. And because effort is so often equated with seriousness, escalation feels responsible rather than reactive.

The trouble is that feeling something happen and something actually changing are not the same process.

Here’s the quieter mechanism underneath all of this.

Your nervous system continuously adjusts its sensitivity based on what it’s repeatedly exposed to. This is why you eventually stop noticing the hum of a refrigerator, the smell of your own house, or the feel of clothes on your skin. The signal didn’t disappear. Your system recalibrated around it.

High-intensity nervous system practices work the same way.

Early on, the contrast they create is significant. Cold exposure, intense breathwork, strong sensory input all stand out sharply against the background of daily life. The nervous system notices immediately. But systems that notice are also systems that learn.

With repetition, the baseline shifts. What once counted as “a lot” becomes normal. The threshold for noticing meaningful change rises. This isn’t resistance or failure. It’s efficiency. The nervous system is doing exactly what it evolved to do: conserve resources by becoming less responsive to what it has learned is predictable.

If you keep turning the volume up, the system becomes increasingly skilled at not being moved by volume.

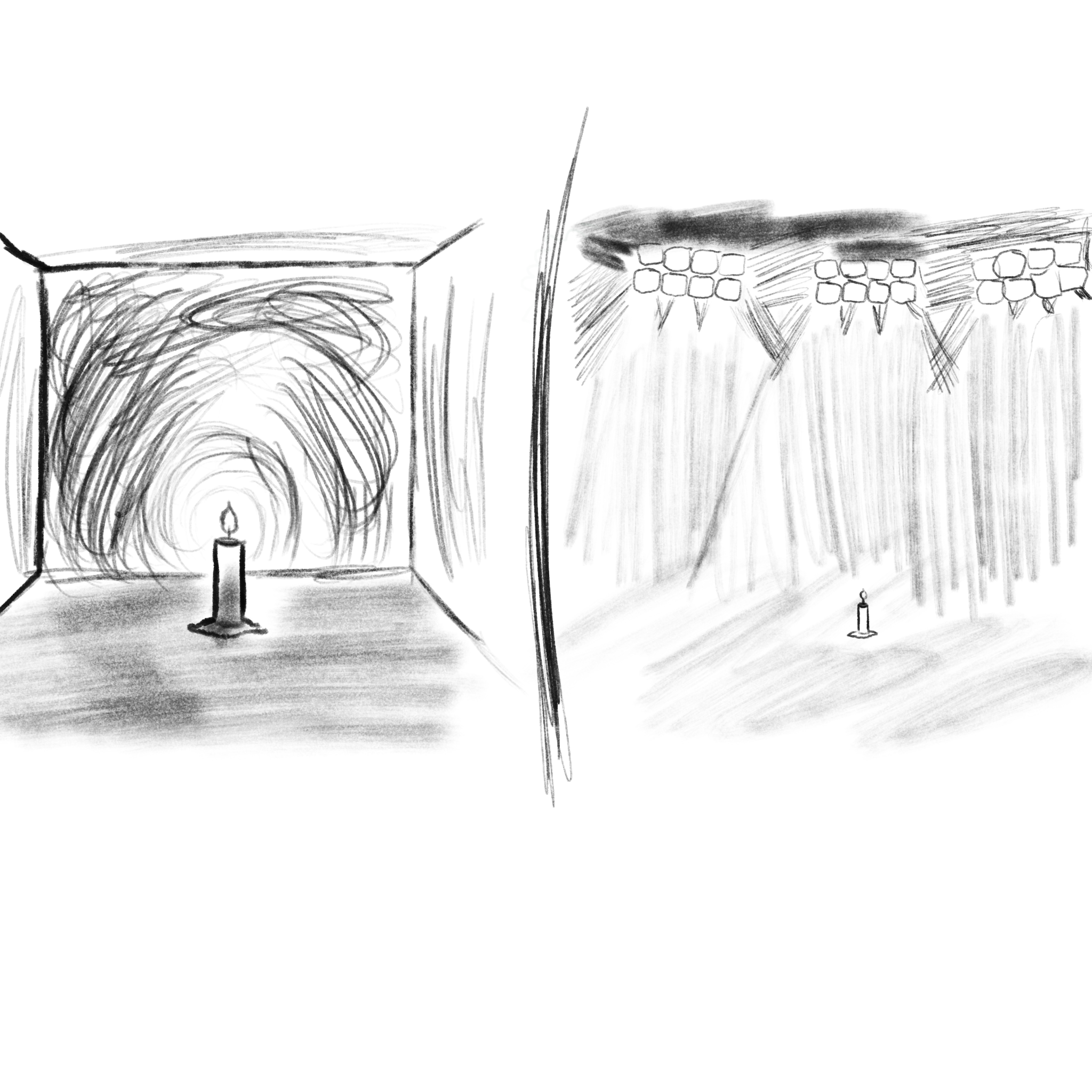

The same light can organize a room or disappear entirely.

Sensitivity depends on where it’s placed.

This is the tradeoff that often goes unseen.

As intensity increases, sensitivity decreases. Not everywhere, but precisely where nuance matters most. The system remains responsive to big, obvious signals while becoming less attuned to smaller ones. Subtle changes in breath, posture, tension, or internal tone stop standing out and begin to blur into the background.

From the outside, this can look like progress. There may be fewer blow-ups, fewer visible swings, a kind of steadiness that reads as resilience.

From the inside, it often feels like delay. You notice what mattered only after it has crossed a threshold that makes choice harder.

And this is where the cost shows up.

You become harder to rattle, yes. But you can also become harder to reach. The partner who’s been trying to say something for weeks. The body that’s been asking for rest in progressively louder voices. The early signs of burnout, depression, or injury, all registering below the threshold you’ve trained yourself to ignore.

What’s being trained in this process isn’t regulation.

It’s endurance.

Endurance is the capacity to tolerate strong internal states without falling apart. That’s a real skill, and in certain seasons of life it’s an important one. But regulation is something different. Regulation depends on discrimination: the ability to detect small shifts early enough to respond cleanly, before escalation becomes necessary.

Endurance keeps you upright in the storm.

Regulation allows you to notice the weather changing.

There’s also a reason intensity is so compelling.

High-intensity practices feel like seriousness. In a culture that equates discomfort with discipline and discipline with virtue, intensity becomes a kind of moral proof, often to ourselves more than anyone else. If it’s hard, it must be working. If it’s subtle, we worry we’re not trying.

This is why the plateau feels like failure even when nothing has actually gone wrong.

So when high-intensity practices stop working, it doesn’t mean you failed. And it doesn’t mean those practices were misguided. It means your nervous system learned the environment it was placed in and adapted accordingly.

At that point, the work usually changes.

Not toward bigger experiences, but toward better timing. Toward restoring contrast. Toward lowering the volume enough for nuance to re-emerge. This kind of work rarely announces itself. There’s no dramatic before-and-after. Often it feels like very little is happening until you realize things are being caught earlier, resolved faster, and requiring fewer hard resets altogether.

This next phase is quieter, and in some ways harder. It asks for attention instead of effort, patience instead of proof.

Sensitivity doesn’t make you fragile.

It makes you early.

And early is where choice lives.

If something that once helped no longer does, that isn’t a step backward. More often, it’s a refinement. An invitation to stop training for extremes and start listening for what shows up long before them.